2020

bodies of stone

In many corners of Brazil, remnants of the past persist, offering a unique experience for a Brazilian photographer like myself. On one hand, there's the empowering ability to witness history unfold before my lens, using my craft as a catalyst for meaningful change. On the other, a profound ache lingers in my chest, stemming from the challenges of experiencing, in my own flesh, what history books merely unveil. The reality is, in a city like Rio, once the capital of the nation and the abode of the Portuguese Royal family for decades, tangible traces endure, offering insights into the historical formation of the country.

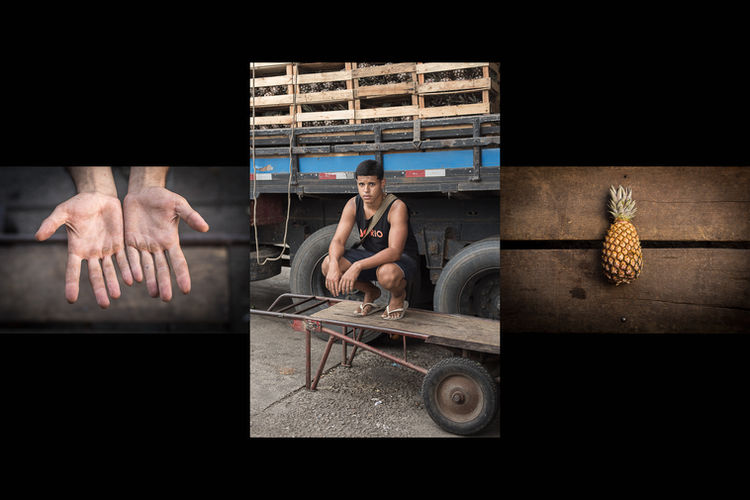

"Bodies of Stone" is a portrait series endeavoring to unveil the individuals behind one of the primary food distribution networks in the country—the food carriers. The title alludes to the central pavilion, "The Stone," not only signifying the toughness of the carriers' bodies but also resonating with remnants linked to a rudimentary past that refuses to fade. The images aim to dismantle social barriers, granting visibility to those who, with calloused hands, bear the responsibility of nourishing the entire region. It's an ode to bodies that may be strong, muscular, thin, old, young, or diverse, yet all resilient as stone. A genuine portrayal of what Rio de Janeiro truly encompasses, far removed from its renowned beaches—an array of faces shaping the Brazilian working class. CEASA embodies suffering and joy, hardship and friendship, heaviness and smiles—nothing more quintessentially Brazilian. It encapsulates an entire country through portraits, entwined with hands and the sustenance they carry. The routine, laden with complexity, demands comprehension. The deeply ingrained political, economic, and social circumstances of the past persist into the present, likely to endure into the future.

In the 1970s, on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro, one of the largest food distribution centers in Latin America was inaugurated—CEASA, an acronym representing supply centers in Brazil. Its objective was to streamline food commercialization and benefit vegetable producers. Beyond the enduring archaic concrete structures, CEASA maintains working relations and conditions rooted in the not-so-distant colonial period. This characteristic isn't unique to CEASA; throughout Brazil, the echoes of the past remain omnipresent. When one arrives at this bustling hub, where around 50,000 people circulate daily, the impact is palpable. The central pulsating pavilion, "Pedra" or "The Stone," houses a diverse array of fresh vegetables, with sounds and smells that leave visitors slightly intoxicated amid a labyrinth of endless box piles. CEASA is a living organism, as one of the local workers aptly describes it. The fleeting sense of lightness can be interrupted at any moment by the shouts emanating from the thousands of food carriers, anchoring one back to the distinctive reality of food distribution in Rio de Janeiro.

Amidst this intricate process, the food carriers, a distinctive profession, emerge prominently. They are responsible for transporting products within CEASA. Given the antiquated and rusty carts, the carriers rely on the strength of their bodies, maneuvering loads ranging from a couple of food carts to tons of potato sacks. At times, the burden exceeds their capacity, yet they persist through corridors and steep ramps, seemingly floating around the distribution center itself. Balancing a cart stacked with boxes towering four times higher than the person becomes an art. Within the distribution center, one finds a diverse spectrum—from young individuals in their initial job to seasoned workers present since the facility's inception. Faces with and without wrinkles, dreams lost amid colossal crates and myriad personalities—CEASA serves as a multicultural sanctuary. There exists a unique language among the food carriers, with a variety of terms that could fill a book, translating into English an insurmountable task. People from all corners of Brazil converge to work, predominantly comprising residents of the favelas surrounding the distribution center. For the vast majority of the peripheral population in Rio de Janeiro, this profession stands as one of the few viable options. The grueling shift begins at 3 am and extends without a fixed endpoint from Monday to Saturday. The more one carries, the more one earns, resulting in continuous figures blending into a blur throughout the corridors.

Being the sole employment option in the region, CEASA also serves as a rehabilitation center for those grappling with alcohol or drug addiction, ex-prisoners seeking social reintegration, and even as a home for those currently experiencing homelessness. At CEASA, there are no prerequisites. Individuals rent a cart and offer their services. Many affectionately describe CEASA as a mother. It is a reflection of the reality of Brazil, where the hand that comforts is the same that punishes. The work is strenuous, with days when they barely earn enough to cover the cart's rent, approximately U$1.5 a day, juxtaposed against days when they may earn up to U$50. Unfortunately, with this volatility and uncertainty about tomorrow, those responsible for carrying food often lack the means to feed their families.

The global COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the situation, with sales plummeting and the ranks of food carriers swelling. Many have lost their jobs, resorting to this profession as their sole income option. In the classic theory of supply and demand, food carriers now find themselves competing for the remaining resources. Despite CEASA being one of the few places operational throughout the pandemic, the current scenario is precarious. The individuals consciously risking their health to ensure food reaches the tables of Rio de Janeiro's population—yes, they are the food carriers. Heroes? In a poignant statement, one of the workers declares, "Here at CEASA, there is work, but no job"—a powerful phrase encapsulating the current precariousness of work under ultra-liberal governments reigning across Latin America. The prevailing perception of CEASA among the populace is that it's the end of the world, yet they remain oblivious to the arduous journey of putting food on their tables. Amid the precarious and archaic circumstances, the facility contends with numerous illegalities. According to one worker, "There are things here that we cannot talk about. There are things that we see, but cannot comment on. I just want to slightly change it for the better"—a modest aspiration shared by all food carriers. CEASA, indeed, is not the end of the world but undoubtedly a world of its own.

.jpg)