krenak reformatory | fragments of an underground memory

ps: better viewied on a desktop

* in progress

1969. Integration.

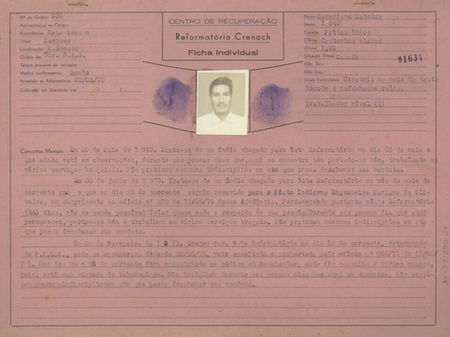

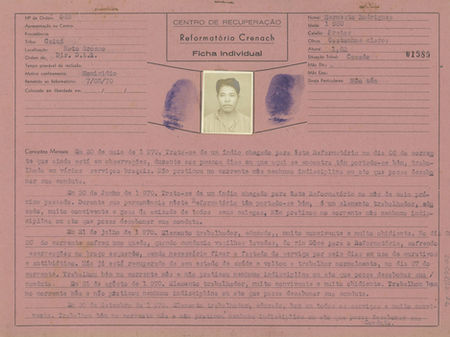

Indigenous communities inhabited crucial lands earmarked for road, railway, and hydroelectric plant construction—an impediment to the Brazilian government's plans, a substantial obstacle to "progress." The solution? Forced confinement and the establishment of the Krenak Reformatory—an exclusive prison for indigenous peoples and one of the most egregious atrocities committed by the country's leaders during the bloody and brutal military dictatorship period that governed Brazil from 1964 to 1985.

The Krenak Reformatory served as a correctional facility for all indigenous peoples deemed problematic by the government. No judges. No right to defense. The prison was erected in the city of Resplendor, Minas Gerais, a territory occupied by the Krenak ethnic group. Over time, indigenous peoples of various ethnicities from across the country were forcibly relocated to the area, not only as prisoners but also as traumatized individuals in search of their disappeared family members.

Prohibited from speaking their own language. Forbidden to perform their rituals. Prohibited from engaging in any activities related to their culture. The reason? Simply to exist. And to be the people who own coveted land.

The situation worsened with the creation of the Indigenous Rural Guard (GRIN), an alternative for the government to resolve relationship issues between soldiers and indigenous peoples. This guard was comprised exclusively of indigenous peoples forced to leave their lands, trained in fighting tactics, and even torture to control the prisoners. Once again, arbitrary use of power, abuse in all spheres.

In 1972, another coup. Local farmers expressed interest in the lands where the prison was located, prompting the military command to transfer the entire population of Resplendor to the city of Carmésia, also in Minas. To forcefully transport all the indigenous peoples, they used closed cargo wagons and handcuffed the most resistant.

Involuntary removals at gunpoint. Internments were analogous to concentration camps. Forced labor. Exile. Sexual violence. Socially degraded ethnicities. Physical and cultural destruction. Torture and violence of all kinds. The horror was so intense in this attempt to decimate the culture of the original peoples that it was likened to the worst crimes against humanity in history. These three episodes constitute serious violations of human rights. The Krenak Reformatory is seen as a judicial aberration—an idea intended solely to commit ethnocide.

Only in the late 1980s was the prison deactivated, and the Krenak indigenous people returned to their land in Resplendor, where the ruins of the old prison now remain. Others, with nowhere to go, stayed in Carmésia. Many members of GRIN, who belonged to the Maxacali ethnic group, sought shelter in new lands, one of them in the city of Ladainha, in the state of Minas Gerais.

2019. Integration.

“Our project for the Indigenous communities is to make them just like us.”

Quote from the ex-president Jair Bolsonaro.

The prison still stands, now in ruins, as do the people. The military government has returned.

Brazil is a country built on untold stories. This project delves into the consequences of an episode during the 1964 military dictatorship. A significant portion of Brazilian society perceives this period as milder compared to other Latin American countries. Our collective memory was largely shaped by the lack of knowledge regarding hidden facts, destroyed documents, and the manipulation of the country's history.

Initiated in 2019, the project seeks to transcend the factual episode, revealing not only the memories of survivors of a series of atrocities but also inspiring the search for the identity of a new generation that must live, quite literally, amidst the ruins. The intention is to explore the psychological aspects of those who were forced to remain in a place scarred by past traumas, attempting to find a sense of place in a world not theirs, yet the only world they have ever known. The project aims to reveal the landscapes, objects, walls, and windows that have become symbols of those who had the courage to endure.

Since its inception, the project has been designed to foster dialogue with society, as the story needs to be revealed. Some concepts inspired the proposed format. First is "underground memory" by Michael Pollak, an Austrian sociologist who defined underground memory in opposition to “official memory” as part of the culture of marginalized, excluded, and oppressed populations. Thus, although symbolically, the project does not aim to be merely a historical document but rather a collection of memory fragments.

In the visual approach, a cloud of fragments was created with symbolic and iconographic photographs. This attempt is to express the different layers of the story that do not follow linearity and contain significant moments that navigate between reality and metaphor. Colors mingle with the black-and-white past. The clouds are divided into chapters, guided in their construction by some crucial words of reference. In the first cloud, we talk about silence and vestiges, in the second about forgetting, obliteration, stricture, and imprisonment, and finally, in the third, about discomfort and resignification.

In each of the clouds, my images are blended with archive images, intending to create a conflict between history and memory. I follow the concept of Pierre Nora, a French historian, who emphasizes contrasts. According to him, memory has roots in concrete elements like space, gesture, image, and object. It is not constant but rather changeable depending on your interlocutor. On the other hand, history is always a problematic and incomplete reconstruction of what no longer exists. Memory is an ever-current phenomenon, a link lived in the eternal present; history is a representation of the past. History seeks to portray them only as victims, but memory shows them as survivors.

.jpg)